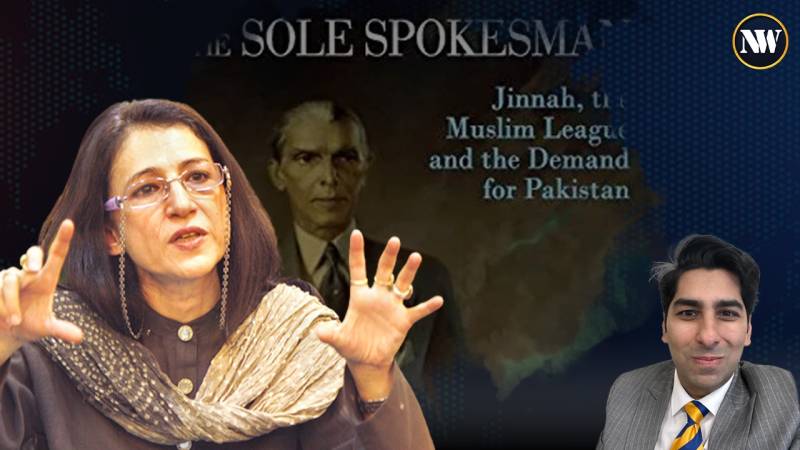

The partition of India in 1947 remains a topic of deep historical significance, sparking debates and discussions about its causes, consequences, and the role of key figures such as Muhammad Ali Jinnah. To gain insights into the intricate dynamics of this period, a recent interview with Dr. Ayesha Jalal, a distinguished historian, and professor of history at Tufts University, provides a nuanced perspective on the historical context, decisions made by individuals, and the misconceptions that often cloud our understanding of this pivotal event.

Dr. Jalal emphasizes the need to avoid deterministic explanations when analyzing the roots of democracy in India and Pakistan post-partition. While acknowledging structural constraints within Pakistan's state formation, she underscores the importance of considering the role of political contingency. Human decisions, often influenced by historical dynamics and individual choices, play a significant part in shaping the course of events. This view challenges the simplistic notion that partition itself predetermined the future trajectory of both nations.

One of the central debates surrounding Jinnah's role is the perception that his stance on partitioning Punjab and Bengal was unclear. Contrary to this misconception, Dr. Jalal asserts that Jinnah consistently opposed the partition of provinces. His emphasis on distinguishing between the partition of provinces and the division of India into Pakistan and Hindustan reveals his strategic thinking. Jinnah aimed to maximize concessions and negotiate effectively with both the British and the Congress by preserving the unity of Punjab and Bengal within Pakistan. This perspective counters the notion that Jinnah was perhaps indecisive about partition.

While some argue that external factors, particularly British influence during World War II, expedited partition, Dr. Jalal underscores the need to acknowledge the internal dynamics and political decisions within the subcontinent. While the British did utilize Jinnah's role during the war to counter Congress's demands, partition was not solely orchestrated by external forces. The complexities of the subcontinent's political landscape and the interactions between various actors played a crucial role in shaping the eventual outcome.

The discussion also sheds light on the concept of secularism in Pakistan and its relationship with Jinnah's vision. Dr. Jalal clarifies that secularism is not the opposite of religion but signifies neutrality in state affairs. Jinnah's vision was multi-dimensional, focused on consolidating political power for the Muslim community rather than promoting an entirely religious or secular state. This challenges the simplistic dichotomy often presented in discussions about Jinnah's intentions and underscores the need for a more nuanced understanding.

The interview also delves into Jinnah's early decisions in governing Pakistan. Dr. Jalal argues that while Jinnah's actions at times exhibited authoritarian tendencies, they were within the constitutional framework. His decisions need to be considered in the context of addressing challenges faced by a nascent state, striving for consolidation and stability. Dr. Jalal points out that blaming Jinnah alone for Pakistan's early challenges obscures larger issues within the country's political landscape.

The interview also addresses the broader debate about whether the partition was primarily influenced by the British or was a result of the inability of Congress and Jinnah to share power. Dr. Jalal suggests that neither viewpoint is wholly accurate. While acknowledging that the British did exploit divisions for their advantage, she emphasizes the shared responsibility of all stakeholders within the subcontinent. The inability to find common ground between Congress and Jinnah contributed to partition, highlighting the intricate web of factors that led to this significant historical event.