With Israel and Iran trading direct blows, all eyes are on the question of how far the conflict can expand and who can stop it. Streets around the world are abuzz with casual talk of World War 3.

In this article, I argue two fundamental points: that the stakes of the current conflict are far bigger than Israel’s occupation of Palestine or even the clash between Israel and Iran. And secondly, as a result of the global situation, the possibilities for further escalation are far greater than any chances of the US and its allies being able to ‘manage’ the situation.

The Stakes: a cold-brewed crisis of the global order

As Israel continues its attempt to carry out ethnic cleansing in Gaza and keep its regional opponents at bay, much of the mainstream commentary has suffered from a nearly fatal flaw. The conflict is presented as a regional one, removed from its global context. At most, the expansion of the conflict is seen as a contest between Israel and Iran.

Reading the conflict in such a limited way, it is natural to treat it as an affair of Israel, Hamas, Iran, the US, various Arab states, and regional movements allied to Iran. Such analysis then falls back on familiar patterns. It restricts itself to looking at regional dynamics that date back to a period from the 1980s to the 2000s. They rely on assumptions of a global Pax Americana – which might wax and wane but is fundamentally here to say. And because it is here, so is Israel and so are the positions of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Arab monarchies, etc. From such a point of view, Iran, Hamas, and their associates in the ‘Axis of Resistance’ are engaged in a quixotic uprising against the regional order – tragically plucky to some, and criminally rebellious to others. This point of view cannot even begin to imagine the stakes that the ‘Resistance Axis’ are playing for.

Today, there is a vast difference between the world that most analysts think about, and the one that we live in. To have any chance of understanding the conflict, an observer must consider the seismic shifts taking place in the global order. The only serious way to describe these shifts is to consider what Chinese President Xi Jinping told his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in March 2023:

“Right now there are changes – the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years. And we are the ones driving these changes together.”

The reader would make a mistake in imagining that Xi refers only to China and Russia when he says “We are the ones driving these changes.” There are stakeholders all over the Global South – and certainly in the MENA region. If one does not situate the current conflict in this context, one cannot begin to understand the strategic thinking of Hamas and the Iran-led ‘Resistance Axis,’ as well as Israel and its backers.

In an interview with Egyptian media outlet Sada Elbalad on 26 October 2023, Hamas leader Khaled Mashal described the stakes of the conflict in a way that is still quite uncommon among the global commentariat. Mashal called for cooperation with “great powers like China and Russia.” He then added:

“For your information, Russia has benefited, because we distracted the US from them and Ukraine.”

This was no stray comment. On 31 October 2023, Mashal built upon the theme, telling Turkey’s TRT network:

“We have friends among the Christians, even the Jews, as well as the global left. We have friends in the world. I am also addressing Moscow and Beijing, Russia and China. Their political position is good […] in the UN […] They can do more. […] This is an opportunity. Moscow and Beijing are striving for an international balance of power that will end unipolar rule. This is your opportunity!"

Given the timing of Operation Al-Aqsa Storm launched by Hamas, it would seem that the armed Palestinian resistance and its helpers in the ‘Resistance Axis’ are not merely aiming at the local Middle Eastern reality of Israeli expansionism. They took note of the global situation to strike a blow at the unipolar US-dominated global order itself.

Chinese policy, for its part, seems well aware of this trend. During the recent hearings at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on Israel's occupation of Palestine, the comments from China signaled what many are interpreting as Beijing’s hardening stance in solidarity with the Palestinian resistance. Chinese foreign ministry legal adviser Ma Xinmin said:

“In pursuit of the right to self-determination, Palestinian people’s use of force to resist foreign oppression and complete the establishment of an independent state is [an] inalienable right well founded in international law.”

While South Africa took the lead in bringing Israel to the ICJ in a separate case on charges of genocide, Brazil, too, has been vocally critical of Israel’s violent occupation and attempts at ethnic cleansing. The stances of these emerging powers from the Global South put them at odds with the generally pro-Israel consensus of the Global North countries.

Naturally, the foreign policy stances of Iran are increasingly geared towards this push towards multipolarity – which resonates with the attitude of China, Russia, and others in the BRICS grouping.

The reader might be justified in wondering at this point: why are all these states and political forces so determined to break out of Pax Americana? Is it not merely an arrangement that arose from the end of the Cold War?

We must return to President Xi’s characterization: the changes he mentioned are not merely three decades. In his view, The matter goes back at least 100 years. What was the world like in 1924? For this, we must refer to historian Domenico Losurdo’s summary of 20th-century history since 1917:

“Before the October Revolution, the entire world was the property of a few capitalist and imperialist powers: Africa was a colony, India was a colony, China was a semi-colony, Indonesia was a colony, and Latin America was a semi-colony (thanks to the Monroe Doctrine). That world was radically changed by the October Revolution, by worldwide anti-colonial revolutions born of the October Revolution. However, when I say that the fundamental essence of the 20th century is the struggle between colonialism and anti-colonialism, I mean it in a deeper sense.”

The whole of the 20th century, including the Second World War and the Cold War, from this perspective, appears as an uprising against Western colonialism– be it the dominance of the Western Allies as liberal colonial powers dominating Asians and Africans, or the German Nazi-led Axis with their colonial objectives against Slavs and Asians. Losurdo sees much of the Soviet and modern contemporary Russian experience as a resistance against being balkanized and colonized by various forces from its west - even though at moments Russia itself has been an expansionist power with serious imperial ambitions.

Naturally, the attempts by various peoples at challenging a world order defined by colonial domination were never appreciated in the Global North, represented today by NATO and its core allies. Movements and states posing a challenge were punished by fierce and excessive violence, which took every form from massacres, invasions, and sponsored coups d’etat, to Cold War strategic competition and economic strangulation under the excuse of fighting a ‘communist threat.’

About this fierce desire to contain and punish those who challenged the colonial world system in politics and economics, Losurdo further notes:

[…] Therefore, Hitler’s failure to build the “German Indies” in Eastern Europe marked the beginning of the liberation of the British Indies [i.e South Asia] as well. Later on, we have the Chinese Revolution, which we can consider perhaps the greatest anti-colonial revolution in the history of the world. And this historical arc concludes with the outright defeat of this first colonial counter-revolution — Hitler’s.

Within this framework, we can detect other attempts at colonial counter-revolution. Immediately after the end of the Cold War we see, for example, Karl Popper, the philosopher of the so-called “Open Society,” openly state that the West “made the mistake of liberating these peoples too soon,” that the colonial peoples were not mature enough to be free. […]”

And yet, the colonized peoples were indeed liberated – too soon for the Western liberal, but too late already for the ‘Third World’ radical. Despite all the mobilization to maintain the colonial hegemony, the desire for sovereignty could never be crushed, nor could violence “change the irresistible historical trend that countries want independence, nations want liberation, and the people want a revolution” – as Mao Zedong put it.

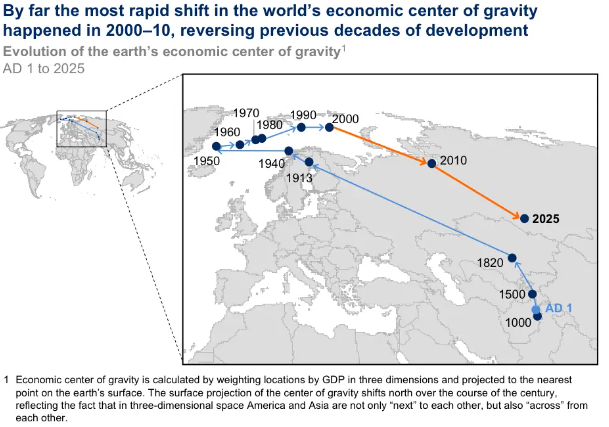

Even with the end of the Cold War and the apparent triumph of a situation favorable to the United States – unipolarity in geopolitics and neoliberalism in economics – the center of gravity of the world economy continued to shift eastwards, towards its original position before the successful colonial rampage of the 18th and 19th centuries. And today, as post-colonial countries regain their economic might, they begin to flex their strategic muscle with increasing confidence.

Imperial Cope: struggling to deal with decline

Today, we live in a world where Western supremacy can no longer rely confidently on its old ways of direct conquest, racial apartheid, and direct plunder. Formerly subjugated countries like China, India, and Pakistan are even armed with nuclear weapons – a world unimaginable to Rhodes, Wilson, Churchill, Reagan, or perhaps even Thatcher. The world’s great factories are in East Asia, and the world’s youth keenly follow cultural trends arising from Africa or Asia on their smartphone apps. Gone are the days of the 1920s, when colonized peoples first learned to wear coats, speak their colonizers’ languages, and win a modicum of decent treatment by contemptuous Westerners. The Global North has been told a story that it is the product of Western civilization, the product of Roman greatness, Christian morality, or Enlightenment insights. Instead, the might of the NATO bloc and its unipolar dominance was lovingly nurtured in two centuries of resource flows from the colonized world to the imperial core.

In an unfamiliar and rapidly changing situation where so many once subjugated races have the money, muscle, and language to ‘talk back,’ the Global North finds it increasingly hard to find political, strategic, and racial meaning for its place in the world. The world itself starts to have no meaning.

As the global balance of power begins to shift in ways unfavorable to the Global North, the narrative being built by the Western mainstream is that of civilized, wealthy liberal democrats versus a world of power-hungry, dysfunctional, ‘authoritarian’ challengers. The EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell best summarised this attitude in 2022:

“We have built a garden. Everything works. It is the best combination of political freedom, economic prosperity, and social cohesion that humankind has been able to build - the three things together.[…]

The rest of the world […] is not exactly a garden. Most of the rest of the world is a jungle, and the jungle could invade the garden. The gardeners should take care of it, but they will not protect the garden by building walls. A nice small garden surrounded by high walls to prevent the jungle from coming in is not going to be a solution. Because the jungle has a strong growth capacity, and the wall will never be high enough to protect the garden.”

Such talk sounds like a desperate coping strategy – and that is precisely what it is. And there is much to cope with after all, a good century or two of absolute Western preeminence in world affairs is coming to an end.

But in a decolonizing world, there is one corner of Asia where Western settlers continue to “make the desert bloom” and treat the natives as they truly deserve. There is one land where the old ways of colonial greatness are still loyally upheld, and where any defiance by Asiatic fanatics and darker peoples is treated with the same firmness as the world of the 1920s. That living theme park of colonial history is Israel: and its psychological importance to Western liberals and conservatives alike is underestimated too often.

Moreover, there is the general role that Israel serves as a beachhead of power projection into an increasingly independent and assertive Asia. Mao Zedong summarised the geopolitical aspect of policing the Asian continent from two directions in 1965, one from the West and one from the East:

“Imperialism is afraid of China and the Arabs. Israel and Formosa [Taiwan] are bases of imperialism in Asia.”

As for the state of Israel, its leadership, intelligentsia, and population are well aware of the strategic and psychological importance of their colonial project for the countries of the Global North. Israel’s messaging towards the Global North countries has tapped into guilt, fear, and self-interest alike. The guilt factor is managed through the Holocaust memory industry, locking some European countries like Germany into unconditional support for Israel. The fear factor is raised by constant Islamophobic propaganda, as well as claims of Israel as being the ‘only democracy’ in the Middle East – with democracy, of course, being a code word for being not Muslim-majority. Israeli narratives point at the self-interest factor for the Global North too, insisting on identifying themselves with the ‘garden’ of the Global North rather than the ‘jungle’ of the challengers. Even as Russia begins to throw its weight behind Iran and the Palestinian resistance, Israel is courting Western liberal approval by supporting Ukraine’s embattled regime.

As matters stand, the US and some of its key allies are very closely committed to the defense of Israel regardless of what it does in occupied Palestinian territories. With US backing, several neighboring Arab states were caught in the middle of normalization with Israel by Hamas’s 7 October 2023 operation. With security guarantees from the greatest war machine in human history, that of the US, what could go wrong for Israel?

We must again look at the global picture as a whole, for a purely MENA-regional analysis cannot explain the challenges faced by Washington DC at this moment.

The US Dilemma: a Hydra of Multipolarity

The most challenging US security commitments at the moment are in three parts of the world. First, in the Pacific, the US is committed to containing China in the South China Sea, shoring up the breakaway regime in Taiwan, and looking to partner with various regional states. Second, the US is committed to containing Russia through NATO expansion in Eastern Europe and the support of Ukraine’s beleaguered war effort for as long as possible. Third, the US is fully committed, as we have explored, to the defense of Israel against any regional challenges.

By launching a fierce counter-offensive against Israel’s longstanding siege of Gaza on 7 October 2023, Hamas was able to set in motion a series of events where Israel finds itself militarily engaged not just in Gaza but also on its northern front with Lebanon’s Hezbollah forces. Already, the possibility of the conflict expanding into Lebanon would require US military support in a situation where Israel is overstretched. With the crisis intensifying, as the Ansar Allah or ‘Houthi’ forces of Yemen stepped in to block the Suez route to ships from pro-Israel countries, they forced the Western countries into the 1860s, before the opening of the canal, when shipping had to sail around the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southernmost tip. The blockade in the Suez route has immense commercial costs for the Global North countries, and to worsen both the injury and the insult, Yemen’s plucky privateers have reached an agreement with China and Russia to allow their shipping through undisturbed.

Israel, of course, has every interest in dragging its NATO allies into war to increase its chances of a successful ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip and then turning its attention to the West Bank and Lebanon. But the US would have to simultaneously support Israel in a larger regional war against Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, while also securing the Suez route and targeting Iraqi militias that align with the ‘Resistance Axis.’

While the UAE and Bahrain would be willing to cooperate with such an effort to restore US supremacy and Israeli impunity in the region, Saudi Arabia appears to be having second thoughts about throwing in its lot totally with Israel. The historic détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran, brokered by China, reduces Riyadh’s incentives to collude with Israel against Iran. Having had his fill of proxy wars with Iran, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has less reason to cooperate with an effort to cut down the ‘Resistance Axis.’ Moreover, Saudi society’s sharp dislike for Israel, no doubt intensified by the hyper-violent decimation of Gaza’s children and adults alike, means that Riyadh will have to pay greater domestic costs for appearing to abandon the Palestinians. The Saudi-Iran détente also brings with it a reduction in sectarian rhetoric sponsored by these two powers – which had long been a boon for Israel’s interests in the region. Today, Israel finds it harder to use anti-Shia animus to compel Saudi Arabia into perpetual hostility with Iran.

Having methodically wrecked the possibility of a two-state solution and is increasingly driven by the ideology of its far-right settler movement, Israel cannot offer the US a path to regional de-escalation. Nor can it provide even a truncated Palestinian statelet to secure normalization by Saudi Arabia and other Muslim-majority countries in Asia.

Israel will not de-escalate unless compelled to. Consequently, the regional forces arrayed against it must respond, leading to further opportunities for escalation. Israel backing off without achieving its stated goals of ‘destroying’ Hamas and defeating Iran would be seen as an obvious victory for the ‘Resistance Axis’ – creating more insecurity for the Israeli state project.

In short, what Israel needs from the US is nothing short of a major unilateral effort to make the MENA region safe for its violent state-building at the expense of Palestinians and others.

If the US commits itself to such a colossal war effort – which would necessarily dwarf any efforts it made during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars combined – it would be bogged down in the MENA region, unable to achieve a concentration of military resources in the South China Sea against its near-peer competitor China, and certainly unable to shore up its Eastern European allies who demand an ever more aggressive NATO stance towards Russia.

On the other hand, if the US were to begin putting serious limits on Israel’s rampage against the population of Gaza, and stop Israeli attempts to expand the war towards Lebanon, Syria, Iran, and beyond, it would be putting Israel’s violent state-building at risk, signaling its unwillingness or inability to uphold major commitments. This would lead to increased assertiveness from Russia, and likely from China, in their respective parts of the world.

Those challenging the US-led world order are certainly not a monolithic bloc or even a loose alliance. But they are keenly aware of the need for rational collusion – as we see from Khaled Mashal’s comments quoted earlier. From the young men defending their neighborhoods in Gaza to the strategic planners in Beijing and Moscow, all those who stand to gain from the weakening of unipolarity are aware of the thin thread by which it currently hangs.

Sooner or later, the US will be decisively called upon to either uphold or abandon one of its three major security commitments in the globe. It will then face the unpleasant choice of protecting a key ally while severely limiting its ability to help others or letting that ally drown so that it can retain the option of acting elsewhere. Neither choice will increase the credibility of its unipolar hegemony.

Knowing all of this, Hamas cast its dice on 7 October 2023 – preferring to bet on the multipolar currents shaking up the world, rather than adopting the Palestinian Authority’s path of facilitating the extinguishing of one’s people as neighboring Arab states normalized with Israel.

But while the US-led colonial-liberal world order finds itself in ever hotter water, many forces all over the Global South eagerly look to gain from the space thus opened. Chinese political scientist Zheng Yongnian describes it memorably:

“Countries are brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order.”

The prospect of a multipolar world means a less unequal global distribution of power – in other words, a democratization of the international system. Like every true democratization, it brings with it more tumult, unforeseen crises, and perhaps newer cruelties. But for those driving this process of multipolarity, the other option is to line up behind a failing Western liberalism that contemptuously describes ancient civilizations and proud peoples as a ‘Jungle’ that threatens the colonial ‘Garden.’

Losurdo underlines the great question of 21st-century international politics, saying:

“And the first objective we must carry out if we seriously consider the problem of democracy is the democratisation of international relations. If a country or a group of countries decide and declare that they have the right to provoke a war — or, worse, a World War — without the authorisation of the [UN] Security Council, they are putting into practice a theory whereby the West has the right to exercise despotism against the rest of humanity. It is open despotism: the US and the West openly declare that they have the right to intervene militarily in every corner of the world. That is despotism."