The US Department of Justice has opened up a criminal investigation into Boeing due to the January 5 door plug blowout incident on an Alaska Airlines flight, operated by a Boeing 737 MAX 9.

On January 5, 2024, Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 took off from Portland International Airport, but as it climbed past 16,000 feet, a door plug blew off from the plane’s fuselage, leaving a gaping hole.

A National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation discovered that the accident aircraft was missing four bolts and fasteners that would usually hold the door plug in place. After the FAA had grounded the 737 MAX 9 and ordered an investigation, United Airlines found missing bolts and fasteners in at least five 737 MAX 9s in its fleet.

The Boeing 737 MAX has been in the news since 2018 for all the wrong reasons. Two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019 led to the loss of 346 lives, caused by a single point of failure and a covertly installed flight control software system called MCAS that pilots and the FAA were unaware even existed.

Once among America’s most respected companies, Boeing has been the subject of intense public and official scrutiny as it battles one safety and quality gremlin after the other. Two Boeing airliners have had their wheels come off during or right after takeoff in the last two months. Even the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has founded himself stranded in Davos due to a technical malfunction with a government operated Boeing 737.

In just the first week of March, three Boeing planes have encountered mishaps – the latest of which involved a 737 MAX running off the end of the runway while landing at Houston, Texas.

The Boeing 737

If you have ever flown more than once on a commercial jet airliner, it is almost certain that you have been on a Boeing 737. It is the most delivered commercial aircraft in the world, with nearly 12,000 sold since Boeing introduced it in 1968.

The market for commercial jet airliners is a duopoly, with European manufacturer Airbus the only real competition to Boeing. Airlines really only have two options when it comes to single aisle narrowbodies – the kind of planes used for nearly all short-haul short-to-medium distance flights - the Airbus A320 family and Boeing’s 737.

The backlog for the two airframers’ models extends for years, with the earliest available delivery slots for an Airbus A320neo all the way in 2028. This means that airlines don’t have many options and will most likely not cancel their orders, even if they want to.

That is precisely why it is a huge deal that Boeing has not only lost market share in the narrowbody segment to Airbus, with the Airbus A320 family having outsold the Boeing 737. Airbus’ A320neo family has logged 10,354 orders, compared to only 6,203 for the 737 MAX.

Boeing may also have squandered something far more significant than commercial success; with the 737 MAX debacle, Boeing seems to have lost the trust of the travelling public and the industry.

MAX pain

On October 29, 2018, a 737 MAX operated by Lion Air crashed into the Java Sea only minutes after taking off from Jakarta, killing all 189 people on board. The crash of Flight 610 did not necessarily prompt questions about flaws in the airframe, because of how ridiculously safe modern commercial aviation is. Accidents are exceedingly rare, and few can be directly attributed to design flaws in the airplanes themselves.

Then, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 fell out of the sky on March 10, 2019 after taking off from Addis Ababa. The flight was also operated by a Boeing 737 MAX. 157 souls perished.

The losses of Flight 610 and 302 prompted a worldwide grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX. In an embarrassing move, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) – usually the gold standard in aviation regulation – was the last to ground the airplane worldwide.

Boeing may also have squandered something far more significant than commercial success; with the 737 MAX debacle, Boeing seems to have lost the trust of the travelling public and the industry.

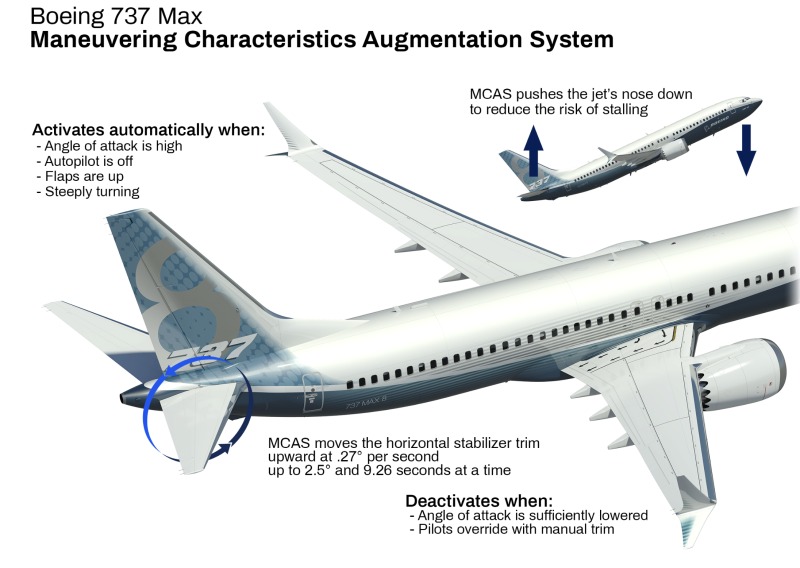

Boeing had engineered the 737 MAX airframe with engines that were unsuitably large for the 1960s era low slung airframe. The resultant aerodynamic changes meant that they installed a software called the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), which would correct the airplane’s behavior in high angle-of-attack flight situations by pointing the nose downwards. The software was fed by data from a single, non-redundant sensor that had failed in the two fatal crashes, and caused the software to erroneously fly the accident aircraft into the ground. Neither pilots nor the FAA was aware of the software’s existence.

The grounding ended in November 2020, having cost Boeing over $20 billion in fines, compensation and legal fees. The airframer also had 1,200 cancelled orders, which represented a loss of over $60 billion at book value.

Airbus’ challenge to Boeing’s bottom line

For decades, the 737 (alongside other Boeing models that have now been discontinued – like the 727 and 757) had been the dominant single-aisle airplane on the commercial jetliner market, until Airbus’ more modern and technologically advanced A320 was introduced in 1988.

Slowly but surely, the A320 began to outcompete the now outdated 737, which was ultimately given a mild overhaul to better compete in 1997. The revamped 737, called the Next Generation family, kept Boeing’s offering competitive.

After the economic downturns of the 2000s, airlines cared about fuel efficiency above all else. With most carriers already operating substantial fleets of either A320s or 737s, they were looking for the airframers to help them cut costs.

The Boeing 737 MAX was Boeing’s hurried and panicked response to the Airbus’ A320. Like Airbus, Boeing also re-engined the 737 Next Generation to produce a more fuel-efficient airliner.

Airbus was the first to market with the Airbus A320neo in 2014. While neo was an acronym for “new engine option,” it was abundantly clear that the improvements that Airbus had made were significant. These included newer engines, greater fuel efficiency, higher payload and better operating economics for airlines. The A320neo was a market success before it even flew, and outsold the 737 so quickly that Boeing had to respond, or it risked losing market position to a clearly superior product.

The Boeing 737 MAX was Boeing’s hurried and panicked response to the Airbus’ A320. Like Airbus, Boeing also re-engined the 737 Next Generation to produce a more fuel-efficient airliner.

Modern commercial airliners are powered by a type of jet engine called the high-bypass turbofan. To make a high-bypass turbofan more efficient requires increasing the engine’s diameter to increase the bypass ratio, which is the ratio of the air that goes around the engine’s combustion chamber to the ratio of the air that goes inside the chamber.

The 737 was originally designed to be low to the ground, so it could be operated at airports without jet bridges and ground handling vehicles. Passengers were meant to board through airstairs, and the baggage compartment was low enough to the ground that ground handlers could load and unload passengers’ bags without needing any support.

This low ground clearance became an issue of concern when Boeing had to install wider diameter engines on the MAX. Airbus did not have this problem, because the A320 was designed with enough ground clearance to wield wider diameter engines. If Boeing increased the landing gear height on the 737 MAX to give enough ground clearance for the newer, wider engines, the Federal Aviation Administration would have deemed it a newer design, and subject the MAX to a more comprehensive certification program. The MAX was intended to pass through the FAA’s radar as a mild evolution of the 737 Next Generation, so that it would not necessitate a newer certification program or pilot retraining, which is a major cost for airlines.

Boeing’s clever workaround for this problem was to install the engines on the MAX further forward and higher on the wing, allowing them to make do with the existing ground clearance. This design change altered the flying aerodynamics of the 737 MAX, making it susceptible to abrupt nose attitude changes mid-flight.

Committed to saving its airline customers pilot training costs to stay competitive against the A320neo, Boeing installed a software on the 737 MAX called the MCAS, or the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System. The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System was designed to push the nose of the aircraft down when the onboard computers sensed that its nose attitude was too high. This would preserve the flying characteristics of the older models.

Boeing thought the system was so benign and irrelevant that it did not even bother to include details about the system’s operations to the FAA. The FAA, keen to assist the American airframer to take the fight to its European competitor, was not too eager to ask tough questions.

The agonizing irony is that putting profits over safety and quality has been bad for the company’s profits as well.

The 737 MAX began commercial service with airlines in 2017. The crashes of Flight 610 and 302 led to the longest ever grounding of a commercial aircraft in US history, and severely dented the public’s faith in the 737 and Boeing.

What happened at Boeing?

Boeing is renowned as one of the world’s foremost manufacturers of commercial airliners, and its airframes have generally had an ironclad safety record. The company’s commitment to quality and safety began to change however, when it merged with McDonnell Douglas in 1997.

In the 1990s, Boeing’s top executives were all engineers. “The folks that designed the airplanes were at the top of the pile. If you look at the pecking order of management today, that’s not the case anymore,” says Ronald Epstein, an ex-Boeing engineer.

Despite Boeing’s penny-pinching corporate culture seeking to save money wherever possible, a disastrous shift away from Boeing’s perfectionist, engineer-led corporate culture has lost the company colossal amounts of money.

The company has been accused of being run with a focus on the bottom line over quality and quantity. Boeing’s corporate culture has been so laser focused on profit maximization that it has led to widespread compromises in quality control, in an industry where even a single loose bolt can have catastrophic outcomes.

The company has routinely laid off scores of workers, and left experienced, unionized staff feeling demoralized and disrespected as management seeks to cut costs wherever possible. Even though the company relies more and more on subcontractors for manufacturing work, it has not managed to turn a profit in five years and declined to set financial targets amidst the Alaska Airlines door plug blowout incident. Even the door plug that blew out of the Alaska Airlines 737 MAX on Flight 1282 was manufactured by Spirit AeroSystems, a Boeing subsidiary that was sold to a private equity firm and now operates as a subcontractor.

Despite Boeing’s penny-pinching corporate culture seeking to save money wherever possible, a disastrous shift away from Boeing’s perfectionist, engineer-led corporate culture has lost the company colossal amounts of money. Boeing’s stock has taken a beating since the fatal Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines MAX crashes in 2018 and 2019, with the company only having reported two profitable quarters since 2019. Even though the S&P500 has risen over 80% in the last five years, Boeing’s stock price has tumbled by as much as 35% during the same time.

The agonizing irony is that putting profits over safety and quality has been bad for the company’s profits as well.

Looking ahead

United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby, while announcing quarterly results in January 2024, questioned the company’s order for 150 of the larger Boeing 737 MAX-10 variant, a larger variant that has yet to be certified by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). “I think the MAX 9 grounding is probably the straw that broke the camel’s back for us,” he said. “We’re going to build a plan that doesn’t have the MAX 10 in it.”

According to Marketplace, Ed Pierson, executive director of the Foundation for Aviation Safety, and former senior manager at Boeing, has said that he refuses to fly in 737 MAX planes.

Pilots of the 737 MAX are told not to run the anti-ice system for more than five minutes in dry air, over concerns of overheating and possible engine failure. “Pilots have told us it’s kind of like being told, ‘Hey, don’t forget to turn your rear defroster off,'” Pierson said. “How many of us have accidentally left the rear defroster on, right?”

Tim Clark, President at Emirates, one of Boeing’s largest customers, has said that the company is in the “last chance saloon,” and that there has been a “progressive decline” in manufacturing standards at the company.

NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy has criticized Boeing's response to the investigation over the Alaska Airlines door plug blowout, saying that Boeing has failed thus far to provide the NTSB with documentation on the manufacturing record for N704AL, the accident airplane. "It is absurd that two months later, we don't have it," Homendy claimed.

Separately, US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has vowed to keep Boeing under strict scrutiny. "We respect the independence of DOJ and NTSB doing their own work, but we're not neutral on the question of whether Boeing should fully cooperate with any NTSB, because they should," Buttigieg told a press conference.

FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker has said that Boeing needs to develop a comprehensive plan to eliminate "systemic quality control issues" within 90 days.