The Democratic Republic of Congo has been ravaged by conflict for the better part of nearly three decades. The country’s mineral rich eastern region of North Kivu is currently witnessing an escalation of conflict between the country’s armed forces and the M23 rebel group. Since the violence broke out in January, hundreds have lost their lives and hundreds of thousands have been displaced.

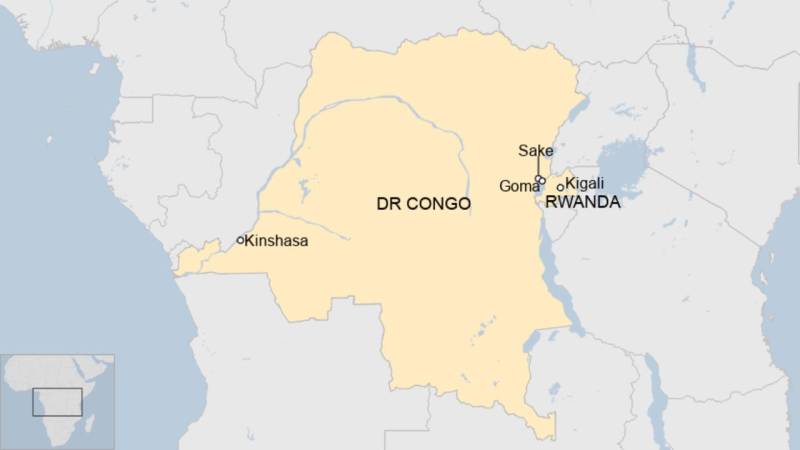

Many fear that the North Kivu region’s capital of Goma, which also houses nearly half a million internally displaced people, could fall to a rapidly advancing M23. The rebel groups are currently stationed in hilly terrain outside the town of Sake, 25 km from Goma. The main roads leading to the city are blocked. If the M23 rebels manage to succeed in capturing Goma, it would be their biggest military success in over a decade.

In the capital city of Kinshasa, Congolese citizens have taken to widespread protests to condemn the international community for its blatant disregard for the conflict in Congo.

The fighting has given rise to one of the world’s most profound humanitarian crises, with UN estimates putting the total number of displaced at over 6.9 million.

Historical context

The roots of conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo can be traced all the way back to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, with the spillover of ethnic conflict in neighboring Rwanda into the DRC’s borders. Rwandan Hutus, which made up 80% of the Rwandan population, fled to the DRC after Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) managed to seize control of the capital Kigali in the wake of the genocide.

In 1996, as the Hutus who had fled to Rwanda began to plan to retake Kigali, they engaged in violent reprisals against Tutsis in both Rwanda and the DRC. The Rwandan government began to arm Tutsi militias in response. Rwanda also accused the DRC dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of harboring Hutu genocidaires, and launched a military offensive in 1996, supported by their allies - Uganda, Eritrea, Angola and Burundi. This was the first Congo war.

After the fighting, the leader of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL), Laurent-Desire Kabila, assumed power as the President of the DRC.

After his ascent to the Presidency, Kabila developed differences with Kagame, the Rwandan president. Rwanda’s support of another rebel group, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), led to a revolt against Kabila’s government in 1998. Another group, the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC) joined the RCD in the revolt, thus starting the second Congo war.

Even though the DRC, Uganda and Rwanda signed a ceasefire agreement in 1999, and the UN deployed the MONUSCO peacekeeping mission, fighting persisted where ethnic tensions had intensified, such as the gold rich region of Ituri.

An alphabet salad of rebel groups

As the DRC’s neighboring countries all developed stakes in the outcomes of the conflict, the ADF, CODECO and CNDP (which later morphed into the M23) emerged as rebel groups armed by regional backers.

There are now close to 140 rebel groups in the DRC, most of which are located in the resource rich north and north-east of the country. The M23, CODECO and ADF remain the most powerful among these.

Who are the M23?

The M23 rebels, often called the March 23 Movement, operate in the North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and are named after a March 23, 2009 ceasefire agreement. As part of the agreement, the DRC government led by President Joseph Kabila, son of Laurent-Desire Kabila, agreed to a pause in hostilities with the Tutsi-majority National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), a rebel group that had gained prominence since the outbreak of the second Congo war.

Part of the ceasefire agreement were requirements for the CNDP to morph into a political party, and for the armed wing of the group to integrate into the Congolese armed forces, the FARDC.

In 2012 however, a faction of the CNDP’s armed wing revolted against the treatment they were subject to in the national military, and formed the M23, as a group dedicated to fighting for Tutsis in the DRC.

The M23 rebels managed to seize Goma in 2012, when they had to be expelled from the region by a UN force authorized to use force. Even though it went dormant not longer after, the M23 reemerged as a potent fighting force in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, and has its eyes firmly set on Goma, a city of 2 million people.

The people of Goma and North Kivu have resorted to forming self-defense groups that fight alongside the FARDC, called the Wazalendos, or patriots. Nearly 40,000 citizens have undergone training and fight as irregular troops alongside the Congolese armed forces.

Rwanda-DRC relations

Tensions between the governments of Rwanda and the DRC have escalated since the reemergence of the M23 in 2022.

Rwanda is widely believed to be supporting the M23 with weapons, ammunition, supplies and funding. Rwanda criticizes Kinshasa for funding the FDLR, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, an ethnic Hutu group that also traces its origins to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Some of the original planners and perpetrators of that genocide are said to be commanding the FDLR, which is committed to carrying out attacks against Rwanda.

Regional attempts for peace

In May 2023, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) approved a military mission for eastern Congo to assist the Congolese government in tackling the armed rebel groups, even as the UN mission stationed in the country – MONUSCO - is expected to leave by December 2024.

Unlike the UN forces, the SADC troops have been authorized to participate in the fighting alongside the Congolese armed forces, and have a mandate to help the armed forces thwart the rebels’ advance towards Goma.