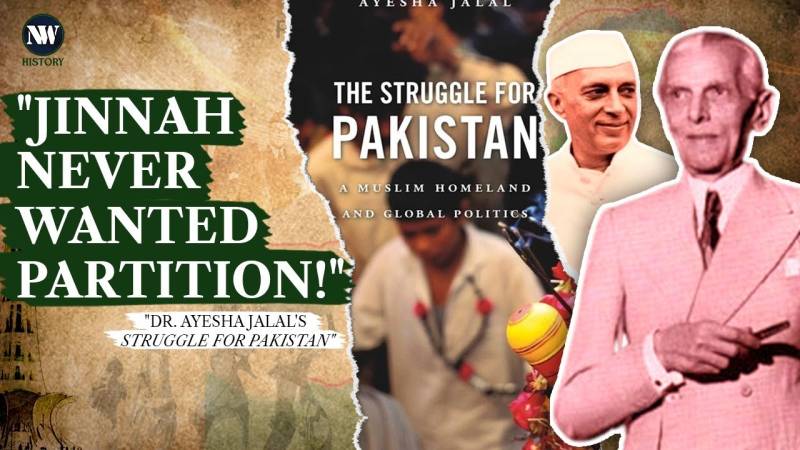

Jinnah and Pakistan’s origin story

Why or how was Pakistan created? At the outset of the book, Dr Jalal addresses the question of how the Muslim community in the subcontinent went from being a minority to a nation, and what did that signify.

Was Pakistan to be an independent nation-state or an autonomous region in a united India?

Six years before Pakistan was created, Jinnah declared that “Pakistan has been there for centuries. It is there today and it will remain till the end of the world.” Significantly, he stated that Muslims had to live as good neighbours and jointly tell the world “Hands off India, India for the Indians.”

Clearly as Dr. Jalal points out Jinnah did not see any inconsistency in raising an apparently separatist demand and still speaking for the Muslim minorities of the entire subcontinent.

She writes: “With even the chief architect of Pakistan ambivalent about the link between Muslim identity and territorial sovereignty, narrating the story of the nation and its nationalism has proven deeply contentious for Pakistanis… the territorial contours of the Muslim homeland would leave almost as many Muslim noncitizens inside predominantly Hindu India as there were Muslim citizens within, compounding the problems confronting Pakistan’s question for an identity that was both Islamic and national.”

She points out that the “the quest for a homeland for India’s Muslims was fundamentally different from the Zionist movement for a Jewish homeland. There was no holy hill in Punjab or Bengal, nor in Sindh, NWFP, or Baluchistan, that beckoned the faithful.”

Jinnah underwent a transformation from an Indian nationalist to a Muslim separatist

About Jinnah, Dr. Jalal writes “A staunch anticolonial nationalist who had devoted his life to the cause of winning freedom from the British, Jinnah in 1916 had hailed the All India Muslim League as a powerful factor for the Birth of United India. Even as late as 1937, he was more interested in forging a political alliance with the Congress Party at the all-India level than striking dubious deals with Muslim politicians in the Muslim majority provinces.”

She points out that when Jinnah finally made the assertion that Muslims were a nation and not a minority in 1940, he made the claim with no references to any Islamic convention.

Instead, Jinnah took his cues from the contemporary internationalist discourse on territorial nationalism and the doctrine of self-determination.

To Jinnah, the political problem of India was not of an intercommunal nature, but was of a distinctly international character and that the only solution was to divide India into autonomous states so that no nation could try and dominate the other and this could then facilitate reciprocal arrangements on behalf of minorities and mutual adjustments between Muslim India and Hindu India.

The fourth paragraph of the Lahore resolution, she points out, referred to the “constitution” in singular to safeguard the interest of both sets of minorities, Muslims in Hindu majority provinces as well as Non-Muslims living in Muslim dominated areas.

This, Dr Jalal says, implied some sort of an all-India arrangement to cover the interests of Muslims in the majority and minority areas. Consistent with this assumption she points out was the conspicuous omission of any reference to either partition or “Pakistan.”

In 1916, at the Lucknow Pact, Jinnah had agreed to barter away Muslim majorities in Punjab and Bengal for better-weighted representation for Muslims in the Hindu majority provinces.

Dr Jalal points out that it was this achievement that became Jinnah’s political vulnerability especially in Punjab and Bengal and in privileging all-India considerations over communitarian and provincial ones, Jinnah misjudged the tenor of politics under the 1919 Montagu Chelmsford reforms. Instead of giving Jinnah and the Muslim League a solid group of Muslim following at the center to represent Indian Muslims, it had given impetus to provincial considerations such as stable governments, which required cross-communal alliances.

Meanwhile, Khilafatist Muslims who were agitating in support of the Ottoman caliphate in Turkey made common cause with Gandhi.

Dr. Jalal writes Jinnah disliked Gandhi’s brew of religion and politics even when while the Khilafat Muslims, such as Shaukat and Mohammad Ali, helped the Mahatma fuse Indian nationalism with Islamic universalism.

In the late 1920s, Jinnah tried to bring together Muslims by positing his famous 14 points. The main stumbling block she says was the fact that Jinnah had to square the concerns of Muslims in majority and minority areas without undermining his own nationalist aims at the all-India centre.

Dr. Jalal points out that Jinnah himself was opposed to the separate electorates because “these would keep Muslims a statutory minority at the all-India level.”

However Muslim politicians by and large wanted separate electorates to maintain their majorities in Punjab and Bengal.

In the 14 points, Jinnah called for the retention of the communal electorates till Muslims voluntarily opted for the joint electorates.

He proposed a federal Indian constitution with residuary powers vesting in the provinces and called for the creation of Sindh and constitutional advancement of Balochistan and NWFP, both Muslim majority provinces.

The Government of India Act 1935 was unacceptable to Muslims in the Hindu majority provinces because it heightened the insecurities of these Muslims. In response to this Jinnah revived the All India Muslim League which had gone moribund.

In March 1934, Jinnah declared that Muslims had to fight for saeguards without losing sign of the wider interests of the country as a whole, which he had always considered sacred. This was six years before the famous Lahore resolution.

Jinnah now stressed the need for Muslims to unite and support a single representative party that would safeguard their interests at an all India center.

To do this, the Muslim League needed to win elections, but the 1937 elections did not clothe Muslim League in that representative status. “Even with separate electorates the Muslim League could poll only 4.4 percent of the total Muslim vote cast.

Barring Bengal where it won a third of the Muslim reserved seats, Muslims snubbed the League in the majority provinces that opted for provincial, and often nonreligious, groupings rather all-India parties.”

Thus, neither the Congress nor the Muslim League could win the Muslim majority provinces.

The Muslim League did much better in the minority provinces, including UP and Bombay, but not well enough to to force a triumphant Congress to forge coalition ministries with the Muslim League.

“If it could emulate Congress’s example in the Hindu majority provinces and bring the Muslim majority provinces under its sway, the League would be able to influence negotiations to determine the constitutional future of independent India… what Muslims needed above all was to overcome limitations of being a minority. One way to resolve the dilemma was to assert that Muslims were not a minority but a nation entitled to being treated on part with the Hindus.”

Dr. Jalal goes on to write: “While the genealogy of the two-nation theory is at best suspect, Jinnah’s need to invoke the idea of Muslim distinctiveness was also based on political and not religious opposition to the Congress.”

Meanwhile the Muslim politicians of Punjab and Bengal despite having defeated the Muslim League came to see the logic of having Muslim League as its spokesman at an all-India level. This led to the Sikandar Jinnah pact in Punjab and agreement between Fazlul Haq and Jinnah in Bengal.

Parallel to this, several schemes had been floated on how the majorities and minorities should share power in an independent India, challenging Congress’ right to indivisible sovereignty but as Dr Jalal points out they did so without altogether rejecting some kind of identification with India.